Modeling Errors – Utah 4 Day week (Working 4)

Utah embarked on a 4 Day week starting in Aug 08 in order to save energy costs. The model for the savings was off by almost all measures. There was little energy savings (13% by Aug 09). However, Utah obtained significant savings in overtime pay – the bulk of all savings was actually savings in overtime pay.

Utah, however, achieved only a sixth of the $3 million it expected to trim on energy costs.

The state couldn’t shut down as many state buildings as it planned on Fridays, officials said, and it didn’t save much by closing the smaller buildings.

Also, the state assumed gasoline for state fleet car use and building utility costs would soar, and it would save as much.

“The state envisioned some energy savings, but that overtime number was not anticipated,” she said Wednesday. New calculations show Utah saved $4.1 million in the first year of a government experiment with a four-day workweek.

State employees were eager to leave after the longer workday, and weren’t inclined to work an extra hour or two.

“They’re getting what they need to get done in 10 hours and going home,” said Angie Welling, spokeswoman for Gov. Gary Herbert.

This is one reason why 4 day weeks should be warranted. The setup (fixed) costs in the premises of an employer, for getting ready to start the daily work is actually a lot larger than what people assume it to be. The setup costs may include costs such as the loss in productivity due to arriving late at work, time spent to drink coffee, visiting the restroom, starting up a computer, and small chit-chat with fellow employees. Moreover, I suspect that an intraday output curve may look like a logit function – low output at the beginning, low output at the end, and higher output for the rest of the time.

However, there may be other costs such as the cost of procrastination. Employees who may be procrastinating can still finish the work within the alloted time without having to be paid overtime hours.

Metrics:

…161,000 fewer hours of overtime worked by state employees, a savings of about $4.1 million,

which would work out to be

1) $25.50 per overtime hours worked.

2) $240 per employee per year in overtime wages saved (assuming 17,000 employees)

3) 9.50 overtime hours per year per employee saved (assuming 17,000 employees)

The baseline model accounted for the savings in gasoline for Utah State ($6 million), energy savings ($3 million), a multiplier effect due to saving of $5 million. These numbers are now suspect. The interim report is published here details that the estimated savings in commute time is 750K gallons of gas (approximately $2 million) .

However, even though the savings in reduction of pollutants (12K tonnes@$40 per tonne Carbon Cap = .5 million), the health benefits of additional recreation time for employees, etc. may be quite small, other benefits may accrue that are difficult to model. All in all, this is a successful program though with significant modeling errors to justify starting the program. It’s good to look at the Nov 2008 Utah Employee survey too for several factors that could have been modeled.

Only a very long longitudinal study will tell if Working 4 is beneficial in the long run. Other costs may be the cost of increasing delinquency rate and lower standardized scores amongst younger children.

Unemployment Forecasts too Optimistic

Elsby, Hobjin and Sahin examine the percentage change in unemployment duration and unemployment inflows. The ramp-up in change in inflow is sobering to even the pessimists. Current unemployment rates forecasts (+9 % by WSJ polled economists by Dec. 2009) are perhaps too optimistic.

A pattern observed in prior recessions has been that increased inflows are often a precursor to increased duration and further increases in unemployment (see Figure 1). This pattern suggests that further weakening of the labour market looms on the horizon, an outcome that would amount to a recession more severe than any seen in the US in the last forty years. This highlights the important need for a successful US stimulus package to stem the tide of a worsening macroeconomic situation in 2009.

Unemployment in the US had already begun to ramp up in early 2007, long before the official recession start date in December 2007 and the vagaries of the financial crisis that came to a head in the latter half of 2008. Figure 1 suggests that the initial impulse to the current recession may not have been the credit crunch, but rather that the credit crunch aggravated already worsening economic conditions.

Comments Off on Unemployment Forecasts too Optimistic

Job Losses Over Post-World War II

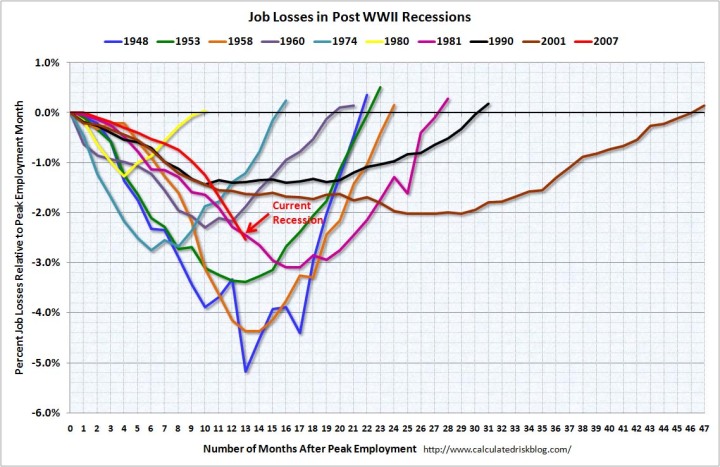

From CalculatedRisk, here is a chart comparing the job losses from prior recessions:

Job Losses (%)

What is striking is that 1) the job losses during the last two recessions lasted far more than previous recessions, 2) the current recession is steep and has a lot deeper to go. If it is as broad based as the prior two recessions, we can expect to see a lost decade that Japan experienced during the 90s.

Comments Off on Job Losses Over Post-World War II

The Stimulus Package

Washington Post has a wonderful graphic on the Stimulus Spending package.

Bankers Paid too Much

Thomas Phillipon and Ariell Resheff study of the employment and wage trends in the financial sector. Their findings are

From 1909 to 1933 the financial sector was a high skill, high wage industry. A dramatic shift occurred during the 1930s: the financial sector rapidly lost its high human capital and its wage premium relative to the rest of the private sector. The decline continued at a more moderate pace from 1950 to 1980. By that time, wages in the financial sector were similar, on average, to wages in the rest of the economy. From 1980 onward, another dramatic shift occurred. The financial sector became once again a high skill/high wage industry. Strikingly, by the end of the sample, relative wages and relative education levels went back almost exactly to their pre-1930s levels.

This was attributed to:

Highly skilled labour left the financial sector in the wake of Depression era regulations, and started flowing back precisely when these regulations were removed…. regulation inhibits the ability to exploit the creativity and innovation of educated and skilled workers. Deregulation unleashes creativity and innovation and increases demand for skilled workers. … however, the compensation of employees in the financial industry appears to be too high to be consistent with a sustainable labour-market equilibrium….Overall, we conclude that bankers were paid about 40% too much in 2006.

We are clearly following the same path (limits to wages of those who seek bailout money, and more regulation). Adios to Banking jobs for the next 6-7 decades. Adios to innovation in the financial sector. So, in the coming decades, which fields will the best and the brightest students pursue? Technology comes to my mind, which is unregulated and requires the skills of a highly educated work force.

Relative Wage and Education in the Financial Occupations

Comments Off on Bankers Paid too Much

Comments Off on Modeling Errors – Utah 4 Day week (Working 4)